A traveller in the Beaubassin/Fort Lawrence region would find it difficult to imagine that this region was the theatre of events that left their mark in the annals of Canada, or indeed of the entire northeastern part of North America,in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. However, this is where the fate of the Acadians and the French colonies in North America played out during this period. But how does one explain how what is today such a peaceful farming region had such a tumultuous past, and moreover, understand that all that now remain of the Acadian presence in the region are the archaeological traces of their settlements? In the following paragraphs, we will try to answer these questions by shedding a little light on the first century of European presence in the Beaubassin/Fort Lawrence region.

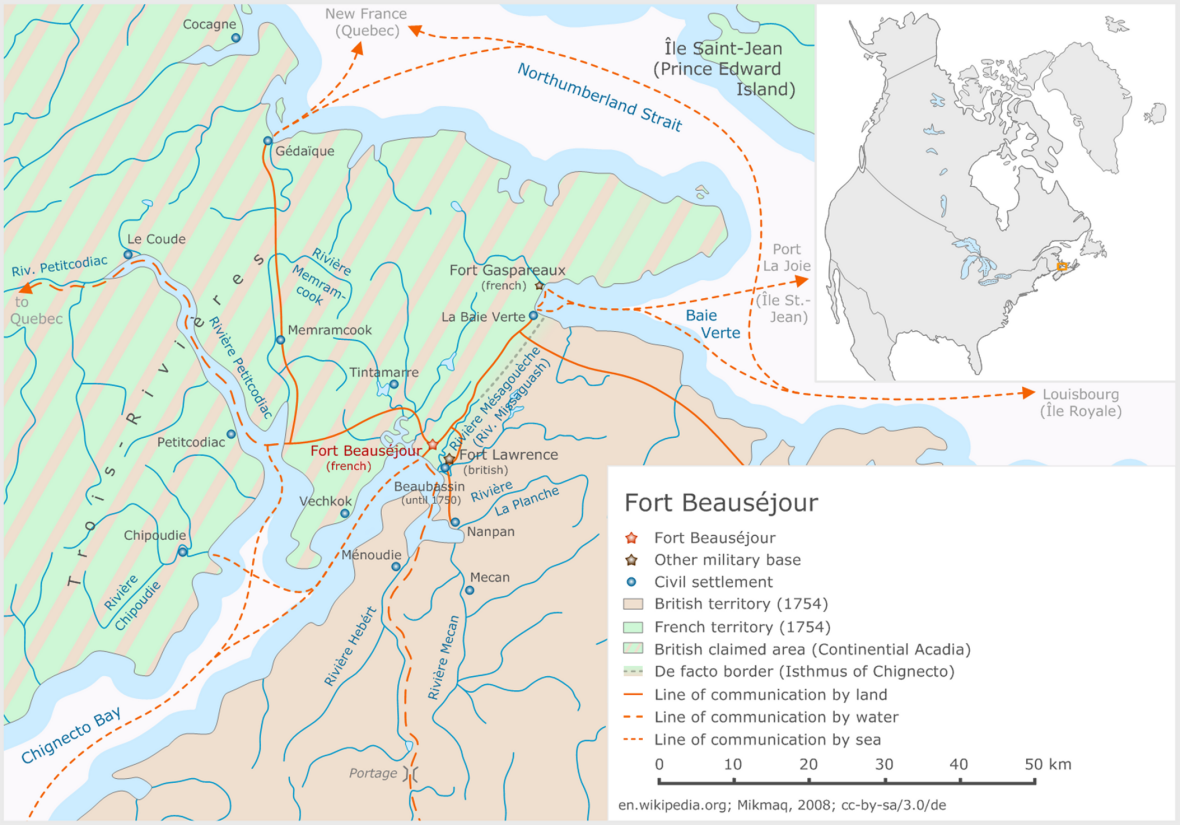

To start off, however, some explanation should be given of the place names in the region. First, there is the Isthmus of Chignecto, which includes all the territory now corresponding to the region around Sackville in New Brunswick and Amherst,including Maccan, Nappan, River Hebert and Minudie, in Nova Scotia. Old French and English documents use both Chignectou and Chignecto to describe this region, though the French also often refer to it as Beaubassin, from the name of the religious parish that included the entire district. Beaubassin also corresponds to the village known today as Fort Lawrence. The Acadians and French also called this village Mésagouèche, from the river of the same name, now known as the Missaguash River, which forms the border between the provinces of New Brunswick to the westand Nova Scotia to the east. Its geographical location gives the Isthmus of Chignecto a major strategic advantage because it is situated between two bodies of water, the Bay of Fundy to the south and the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the north. Since time immemorial, First Nations communities have used the waterways and portage routes connecting these two shores. Because of the region’s large expanses of marshlands, game was abundant and the high tides supplied the fish and shellfish necessary for the Aboriginal people’s diet. Indeed, the first Europeans to come to the region benefited greatly from their knowledge of the area and realized the region’s strategic importance. In any case, although the first contacts between these two peoples were in the sixteenth century, when Portuguese and other explorers visited the region, only in the seventeenth century, when the French arrived in Acadia, did the Isthmus of Chignecto region attract its first European colonists, and they settled here quite late. Colonists from the Port Royal region began to settle in the area in the 1670s to exploit its immense marshlands. Other colonists of French origin settled there at the same time, but they came from the St. Lawrence River area or Canada, by way of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the portage connecting it to Beaubassin, the name given to this new colony. These colonists accompanied their seigneur, Michel Le Neuf de LaVallière, who had obtained a large grantor seigneurie from the governor of Canada or New France, who believed that the Isthmus of Chignecto region was under his jurisdiction. Thus, even before the English or British arrived there, there was a certain ambiguity about this region that straddled two French colonial administrations.

To start off, however, some explanation should be given of the place names in the region. First, there is the Isthmus of Chignecto, which includes all the territory now corresponding to the region around Sackville in New Brunswick and Amherst,including Maccan, Nappan, River Hebert and Minudie, in Nova Scotia. Old French and English documents use both Chignectou and Chignecto to describe this region, though the French also often refer to it as Beaubassin, from the name of the religious parish that included the entire district. Beaubassin also corresponds to the village known today as Fort Lawrence. The Acadians and French also called this village Mésagouèche, from the river of the same name, now known as the Missaguash River, which forms the border between the provinces of New Brunswick to the westand Nova Scotia to the east. Its geographical location gives the Isthmus of Chignecto a major strategic advantage because it is situated between two bodies of water, the Bay of Fundy to the south and the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the north. Since time immemorial, First Nations communities have used the waterways and portage routes connecting these two shores. Because of the region’s large expanses of marshlands, game was abundant and the high tides supplied the fish and shellfish necessary for the Aboriginal people’s diet. Indeed, the first Europeans to come to the region benefited greatly from their knowledge of the area and realized the region’s strategic importance. In any case, although the first contacts between these two peoples were in the sixteenth century, when Portuguese and other explorers visited the region, only in the seventeenth century, when the French arrived in Acadia, did the Isthmus of Chignecto region attract its first European colonists, and they settled here quite late. Colonists from the Port Royal region began to settle in the area in the 1670s to exploit its immense marshlands. Other colonists of French origin settled there at the same time, but they came from the St. Lawrence River area or Canada, by way of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the portage connecting it to Beaubassin, the name given to this new colony. These colonists accompanied their seigneur, Michel Le Neuf de LaVallière, who had obtained a large grantor seigneurie from the governor of Canada or New France, who believed that the Isthmus of Chignecto region was under his jurisdiction. Thus, even before the English or British arrived there, there was a certain ambiguity about this region that straddled two French colonial administrations.

To start off, however, some explanation should be given of the place names in the region. First, there is the Isthmus of Chignecto, which includes all the territory now corresponding to the region around Sackville in New Brunswick and Amherst,including Maccan, Nappan, River Hebert and Minudie, in Nova Scotia. Old French and English documents use both Chignectou and Chignecto to describe this region, though the French also often refer to it as Beaubassin, from the name of the religious parish that included the entire district. Beaubassin also corresponds to the village known today as Fort Lawrence. The Acadians and French also called this village Mésagouèche, from the river of the same name, now known as the Missaguash River, which forms the border between the provinces of New Brunswick to the westand Nova Scotia to the east. Its geographical location gives the Isthmus of Chignecto a major strategic advantage because it is situated between two bodies of water, the Bay of Fundy to the south and the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the north. Since time immemorial, First Nations communities have used the waterways and portage routes connecting these two shores. Because of the region’s large expanses of marshlands, game was abundant and the high tides supplied the fish and shellfish necessary for the Aboriginal people’s diet. Indeed, the first Europeans to come to the region benefited greatly from their knowledge of the area and realized the region’s strategic importance. In any case, although the first contacts between these two peoples were in the sixteenth century, when Portuguese and other explorers visited the region, only in the seventeenth century, when the French arrived in Acadia, did the Isthmus of Chignecto region attract its first European colonists, and they settled here quite late. Colonists from the Port Royal region began to settle in the area in the 1670s to exploit its immense marshlands. Other colonists of French origin settled there at the same time, but they came from the St. Lawrence River area or Canada, by way of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the portage connecting it to Beaubassin, the name given to this new colony. These colonists accompanied their seigneur, Michel Le Neuf de LaVallière, who had obtained a large grantor seigneurie from the governor of Canada or New France, who believed that the Isthmus of Chignecto region was under his jurisdiction. Thus, even before the English or British arrived there, there was a certain ambiguity about this region that straddled two French colonial administrations.

To start off, however, some explanation should be given of the place names in the region. First, there is the Isthmus of Chignecto, which includes all the territory now corresponding to the region around Sackville in New Brunswick and Amherst,including Maccan, Nappan, River Hebert and Minudie, in Nova Scotia. Old French and English documents use both Chignectou and Chignecto to describe this region, though the French also often refer to it as Beaubassin, from the name of the religious parish that included the entire district. Beaubassin also corresponds to the village known today as Fort Lawrence. The Acadians and French also called this village Mésagouèche, from the river of the same name, now known as the Missaguash River, which forms the border between the provinces of New Brunswick to the westand Nova Scotia to the east. Its geographical location gives the Isthmus of Chignecto a major strategic advantage because it is situated between two bodies of water, the Bay of Fundy to the south and the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the north. Since time immemorial, First Nations communities have used the waterways and portage routes connecting these two shores. Because of the region’s large expanses of marshlands, game was abundant and the high tides supplied the fish and shellfish necessary for the Aboriginal people’s diet. Indeed, the first Europeans to come to the region benefited greatly from their knowledge of the area and realized the region’s strategic importance. In any case, although the first contacts between these two peoples were in the sixteenth century, when Portuguese and other explorers visited the region, only in the seventeenth century, when the French arrived in Acadia, did the Isthmus of Chignecto region attract its first European colonists, and they settled here quite late. Colonists from the Port Royal region began to settle in the area in the 1670s to exploit its immense marshlands. Other colonists of French origin settled there at the same time, but they came from the St. Lawrence River area or Canada, by way of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the portage connecting it to Beaubassin, the name given to this new colony. These colonists accompanied their seigneur, Michel Le Neuf de LaVallière, who had obtained a large grantor seigneurie from the governor of Canada or New France, who believed that the Isthmus of Chignecto region was under his jurisdiction. Thus, even before the English or British arrived there, there was a certain ambiguity about this region that straddled two French colonial administrations.The beginning of the new colony was marked by numerous problems, including some with the seigneur of Beaubassin, who served as Lieutenant-Governor and Governor of Acadia. One colonist was tried on charges of sorcery, while another colonist was accused of having gotten the daughter of the seigneur, Governor La Vallière, pregnant. This led to the departure of several of the families who had come from Canada. During the War of the League of Augsburg and the War of the Spanish Succession at the turn of the eighteenth century, the new settlement at Beaubassin was sacked twice, in 1696 and1704, by militia men from New England on incursions into Acadia. As well, in 1710 Port Royal, the capital of this French colony, fell definitively into British hands. With the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, France ceded Acadia as defined by its former boundaries to Great Britain. Were the colony at Beaubassin and the surrounding region within these former boundaries, since they were considered to be part of Canada? This ambiguity in the minds of the settlers in the region did not bode well for the new British administration at Port Royal. First, the distance between them made the British colonial authorities’ task more difficult. Apart from the independent spirit that had developed among the settlers in the Beaubassin region, the authorities had to deal with a population of rather dubious allegiance. When the authorities tried to make the settlers swear an oath of allegiance to the King of Great Britain, they were met with a categorical refusal. After a few years of negotiations, they swore a conditional oath that released them, among other things, from bearing arms against the French and the Aboriginal people in time of war. Moreover, since they were used to trading with New England under the French administration, the settlers in Beaubassin turned their eyes toward the new French colonies in the region, Île-Saint-Jean and Île-Royale and especially the fortress town of Louisbourg, established in the early 1720s.

During the long period of peace between France and Great Britain lasting until the mid-1740s, the Beaubassin region under went great expansion because of this trade, to the great displeasure of the British authorities in Port Royal. In 1744, the stakes changed radically with the declaration of the War of the Austrian Succession, which again saw Great Britain and France on opposite sides of a conflict.The French mounted four expeditions against Port Royal to become masters of their former colony, Acadia, and almost all of them were staged from Beaubassin. The French troops even established a permanent base in the region to ensure the success of these plans for reconquest. During the negotiations leading to the signature of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which put an end to the War of the Austrian Succession in 1748, it was agreed to set up a commission to settle once and for all the question of the former boundaries of Acadia, left hanging after the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht some 25 years earlier. Before this commission even had time to sit, the French and British wanted to strengthen their positions in the region in order to further their claims.Thus, in the fall of 1749, French troops from Canada built a little blockhouse at Pointe-à-Beauséjour, on the west bank of the Mésagouèche River, claiming all the territory to the west and north as part of Canada or New France. The British, on the other hand, were not comfortable with the Acadians settlers, those in the Beaubassin region as well as elsewhere in Acadia, who, according to them, were not subjects who could be counted on in case of war because of the neutrality they had shown during the French expeditions against Port Royal or the colony during the War of the Austrian Succession. Therefore, they decided to adopt a new policy or a different approach toward this population by requiring the settlers to swear an unconditional oath of allegiance that would force them to bear arms against any aggressor, whether French or Aboriginal. Finally, to ensure better control over this population that they considered disloyal, they decided to build fortifications throughout the colony starting, in the summer of 1749, with the founding of Halifax, the new seat of the British administration. More fortifications were built in the Grand Pré or the Minas Basin area, and Beaubassin was to be next when it was learned that the French were already there. In the spring of 1750, a British expedition was sent from Halifax, under the command of Major Charles Lawrence, to drive the French from the isthmus. Since there was no well-developed network of roads, the expedition arrived by sea to face the French troops, supported by their Aboriginal allies and the Acadians from the region of Beaubassin. Faced with a well-armed opponent, Lawrence and his troops had to retreat and temporarily accept the presence of these so-called intruders on lands that they believed belonged to them. At the approach of the British fleet, the French had given the order to burn the village of Mésagouèche or Beaubassin, telling the settlers to cross to the west bank of the Mésagouèche River into the territory that they claimed as part of Canada or New France. This event, along with those surrounding the new British colonial policy in Acadia, caused the exodus of thousands of Acadians and thus represents the beginning of the Grand Dérangement or the Great Upheaval, since nearly one fifth of the total population of Acadia was disturbed in 1749-1750, more than five years before the Deportation. In September 1750, Major Charles Lawrence commanded another expedition,much stronger this time, which the French troops could not resist. The British managed to get as far as Beaubassin and erect a fort, which they called Fort Lawrence, on or near the site of the parish church that had been burned in the spring with the rest of the village.

The French then gave the order to burn all the other villages to the east of Beaubassin, and thus in British territory, swelling the ranks of the families who been living as refugees on the west bank of the Mésagouèche River since spring. To make the situation even worse, the entire harvest was burned in the barns. Even though the settlers had brought their cattle across the river with them, they had no more fodder for them and had to slaughter them through the following fall and winter. Without this important source of food, they had to live on the charity of the King of France for the next five years, that is, until the fall of Fort Beauséjour, built by the French in 1751. In the meantime, this population of Acadian refugees continually complained to the French authorities, who had forced them to leave their settlements and their lands,which were now on territory recognized as British by the French, and to which the refugees wanted to return.The Acadians found themselves this difficult situation until the beginning of June 1755, when a British expedition commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Monckton and made up of around 2,000 militiamen from New England and a few hundred regular British troops arrived before Fort Beauséjour. The ensuing siege only lasted two weeks before the 150 or so besieged regular French troops and 150 Acadians laid down their arms. Shortly thereafter, in Halifax, the Acadians’ fate was sealed by Lieutenant-Governor Charles Lawrence and his council: the entire Acadian population, not only in the Beaubassin region but also all over Acadia,would be deported to the Anglo-American colonies. Thus on August 11, 1755, over 400 Acadian men and boys were arrested and imprisoned in forts Lawrence and Beauséjour, now called Fort Cumberland.Over two months later, a little over 1,000 men, women and children sailed away on ships transporting them to the colonies of Georgia and South Carolina. Most of them never saw the land of their birth again.However, many Acadians from the Beaubassin region avoided deportation in 1755 and took refuge in French territory,especially Île-Saint-Jean. Others escaped to Canada or remained in what is now the province of New Brunswick, waging a partisan resistance against the British troops stationed at Fort Cumberland and elsewhere. After the fall of Québec in the fall of 1759, however, several hundred of these resistance fighters surrendered with their families to the British authorities.Thus over 300 Acadians were kept prisoner in Fort Cumberland or in makeshift shelters built near the fort. They remained in this precarious situation until the late 1760s, when they were allowed to settle elsewhere, including the Memramcook area in southeastern New Brunswick and Cumberland County in Nova Scotia. In this way, nearly a century after their ancestors settled in the Beaubassin region in the1670s, these Acadians were able to lay the foundations of a new Acadia.Today, all that remains of the Acadians’ stay in Beaubassin/Fort Lawrence are the traces of their village, burned in the spring of 1750. Thanks to Parks Canada’s public archaeology program, we are uncovering the remaining evidence of this Acadian presence in Beaubassin/Fort Lawrence before 1755.

No comments:

Post a Comment